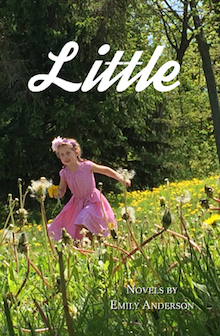

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Emily Anderson writes about Little: Novels from BlazeVOX.

+

Four years ago I started erasing Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House novels. I didn’t have a book in mind. I just wanted an excuse to spend time thinking about Little House and playing with Wilder’s language, with all the pretty cakes, shiny tin cups, and “boughten” sofas.

Four years ago I started erasing Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House novels. I didn’t have a book in mind. I just wanted an excuse to spend time thinking about Little House and playing with Wilder’s language, with all the pretty cakes, shiny tin cups, and “boughten” sofas.

I’ve been obsessed with Little House (both the books and the TV show) since I was a kid. I used to roam around with a brown skirt over my head, pretending I had long, straight dark hair like Laura Ingalls. This was back when Reagan was in the White House. He watched Little House on the Prairie, too. He sat in the White House residence tapping his foot to the show’s theme song, sometimes tearing up. Seriously. Gross. I hate that I share the prairie with him.

As an adult, I once co-hosted a Little House on the Prairie party with my friend Amanda Marbais. We wore bonnets, served baked beans and designed a Little House drinking game. I don’t remember all the rules, but here’s the gist: watch the show and drink every time someone falls down or cries. Drink every time Pa is right. Drink twice if Pa is right and crying or falling. Pretty soon, you’ll stop noticing that the baked beans are slightly crunchy.

While I connect Little House to that open meadow of childhood imagination and to the playful, snarky part of me (the prickly adult version of “playing pretend”) I also see Little House as intimately connected to violence. Historian Waziyatawin Angela Wilson describes Little House on the Prairie as a narrative that “transform[s] the horror of white supremacist genocidal thinking and the stealing of Indigenous lands into something noble, virtuous, and absolutely beneficial to humanity.” Wilder figures genocide as a necessary evil, part of a nation’s coming of age, a romantic loss of innocence, a young girl’s growing up. As Ronald Reagan might say, “It’s morning again, in America…so let’s forget about last night.” Little: Novels emerged from my own ambivalence about who I am, what I love, where I feel I belong, and what I feel belongs to me.

One of the things I love about the Little House novels are Wilder’s detailed descriptions of how to do things like mold bullets or make butter. (I discovered as an adult that Wilder’s contemporary, Zitkala-Sa, also does this how-to beautifully in her American Indian Stories). So I thought I’d share some erasure how-to and talk about the techniques I used when I was trying to figure out what to do with Wilder’s The Long Winter. Set in white-out winter conditions, The Long Winter is in some ways a novel about erasure itself. None of these techniques I’m describing generated writing that made it to the final version of the book; this an account of my false starts, my getting lost in the blizzard between the house and the barn, Wilder’s Little House series and my Little: Novels.

Scrub the sink until the enamel shines.

Place your book in the sink. Pin it open with forks.

Walk down to CVS for a bottle of bleach.

Paint your book with glue.

Pour sugar.

Look! Your very own little cake.

Interleave your book with puffy sheets of bubble wrap.

Close the book and set it on the floor.

Jump.

Throw your book out the window into the snow.

Decide to wait until spring.

Get bored. Go find your damp book.

Order a special “study stand” from Amazon

Imagine re-typing the entire book without getting a neck ache

Do nothing. Wait for your special stand.

Paint your nails white. Soak the book in acetone.

Press your nails to the wet page.

Wait for the letters to float off the page and adhere to your fingers.

Wait forever. (Nothing happens).

Retype every line of dialogue in the novel.

Put a heating pad on your neck.

Delete all the dialogue.

Leave the dialogue tags, so your text looks like this:

She exclaimed. She went on. She asked, she praised him, she decided. She almost whispered, but she answered. He declared. She asked him. He counted up.

Re-read Mina Loy’s story “All the Laughs in One Short Story by McAlmon”

Re-watch this video of Michael Landon laughing.

Open a new Word document. Start over.

+++