Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Maud Casey writes about The Man Who Walked Away from Bloomsbury.

+

My most recent novel is “inspired by” (in TV docudrama parlance) a 19th century French psychiatric case study. It required a lot of earnest research and a lot of crashing around. I like to think it’s always that way when a fiction writer is starting a conversation with a particular moment in history and with a particular historical figure, however obscure. Part hitting the books and part flailing around, with an emphasis on the latter.

My most recent novel is “inspired by” (in TV docudrama parlance) a 19th century French psychiatric case study. It required a lot of earnest research and a lot of crashing around. I like to think it’s always that way when a fiction writer is starting a conversation with a particular moment in history and with a particular historical figure, however obscure. Part hitting the books and part flailing around, with an emphasis on the latter.

It was Ian Hacking’s amazing book, Mad Travellers: On Transient Mental Illness that introduced me to the real Albert Dadas. Hacking’s book, which began as a series of lectures, describes—and this is a gross reduction of his nuanced take—the way a particular psychiatric diagnosis arises at a particular moment in history, for cultural, nationalistic, and social reasons. It features the case of Dadas as an example of a diagnosis that appeared and then disappeared. Dadas was the first diagnosed fugueur (which was the title of my novel until a friend gently suggested I should be able to pronounce the title of my novel). Once a primary diagnosis, it now appears in the DSM as a symptom (fugueur is the origin of fugue state). In any case, Dadas brought himself to a Bordeaux asylum in 1886 because he had been walking in a semitrance state, throughout Europe, for years. He was exhausted; he was in anguish. From the moment I read this excerpt from Dadas’ doctor’s case notes, I was hooked (or sunk, depending on how you look at it):

It all began one morning when we noticed a young man . . . crying in his bed in Dr. Pitre’s ward. He had just come from a long journey on foot and was exhausted, but that was not the cause of his tears. He wept because he could not prevent himself from departing on a trip when the need took him; he deserted family, work, and daily life to walk as fast as he could, straight ahead, sometimes doing 70 kilometers a day on foot, until in the end he would be arrested for vagrancy and thrown in prison.

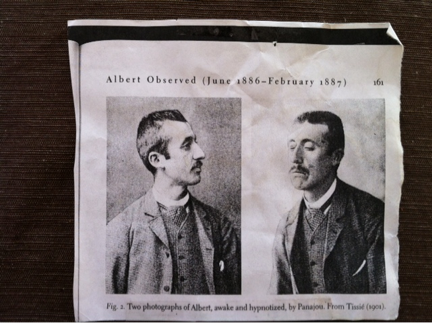

But it was the translated documents in the back of Hacking’s book — including transcriptions of Albert’s response (often under hypnosis, the medical intervention du jour) to questions about his mysterious travels — that haunted me, causing me to return to the book years after I read it. The strange, lyrical voice of a man lost in the world, lost to himself, describing his travels with a funny mixture of bemusement and bafflement. “One fine day I awoke on the train,” he says. “I was at Puyoo. ‘Well,’ I said to myself, ‘yet another escape. What a calamity!’” Again and again, in his accounts, he would find himself, discover himself, not knowing how he got there, somewhere else entirely. This was where my research started, with the language. I made a study of the way this man spoke until his phrases were stuck in my head like a song, a song that was always entwined with the pictures of him “awake and hypnotized.” I carried a copy of these pictures with me, a kind of love letter, for the next seven years. Here they are:

That big head. That sweet face. Even in hypnosis, maybe especially then, such earnestness! Oh, Albert. So it began with the odd song of Albert but I pretty quickly realized I would need to learn something about the early days of psychiatry, the geography of Europe, the history of the bicycle, for cripes sake (Dr. Tissié, Dadas’ doctor, as it turned out, was a big cycler, the first doctor for the Bordeaux cycling club). I might need to know something about the beginnings of mass tourism and something about the flâneurs, and possibly I’d need to bone up on the Franco-Prussian War. One of the many useful books I would eventually read was Edward Shorter’s Psychosomatic Illness: From Paralysis to Fatigue. Let’s just say that at the beginning of this project I was headed in the other direction. I had what can most accurately be described as a mini freak-out. Who was I to embark on this project? I who had never written historical fiction before? Why had my imagination dragged me to France? To the nineteenth century? To a man whose diagnosis I couldn’t even pronounce? So…that happened. But the imagination wants what the imagination wants.

Hacking’s bibliography was a good place to start. In the beginning, I read and read and read. It was a great way to avoid that feeling of paralysis. I spent time in the Library of Congress — a Metro ride away — reading obscure 19th century medical articles in French. My French is pretty rusty or, rather, it was always rusted. Je me débrouille, as they say. And I do mean they. That word is really hard to pronounce too. I spent a lot of time thinking about how generous the Library of Congress was to loan me those old books. Didn’t they suspect I might accidentally tear a page? Didn’t they suspect my compulsion — I fended it off, I promise! — to scribble in the pages of these beautiful books with my pencil? Why did these people trust me? There was a lot of projecting going on in the Medical Library that summer. Still, I got a lot of reading done. Here are a few books from one of the piles that still teeters in my home: Stephen Kern’s The Culture of Time and Space (1880-1918), Alan Gauld’s A History of Hypnotism, Hippolyte Bernheim’s Hypnosis and Suggestion in Psychotherapy, Piers Bierdon’s Thomas Cook, Jan Goldstein’s Console and Classify, Daniel Paul Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, Christopher S. Thompson’s The Tour de France, Henri Ellenberger’s The Discovery of the Unconscious, Georges Didi-Huberman’s The Invention of Hysteria, Asti Hustvedt’s Medical Muses: Hysteria in 19th Century Paris, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. Some of these books I read more than once; some of these books I dipped into; some were, ahem, less read than others (Thomas Cook and The Tour de France were both fascinating but after I got what I needed, they became more escape than research).

I read Rebecca Solnit’s invaluable Wanderlust: A History of Walking. I dipped into Rousseau’s Reveries of a Solitary Walker. I returned to some of the famous walkers I knew and loved — Robert Walser and his novella The Walk, for example. I read until I felt I knew enough to unhitch the story from history. And then, slowly, slowly (did I mention slowly?), I began to write. At some point I decided, in part because Dadas is a name whose weight fiction cannot bear, that I would refer to Albert by his first name, and to refer to his doctor as the Doctor and to refer to the doctor who shares a lot in common with Jean-Marie Charcot, the neurologist who made hysteria famous, as the great doctor. At first, this felt temporary but then it started to make sense. I wanted a little distance and I wanted to be deliberate about it, to signal that distance to the reader.

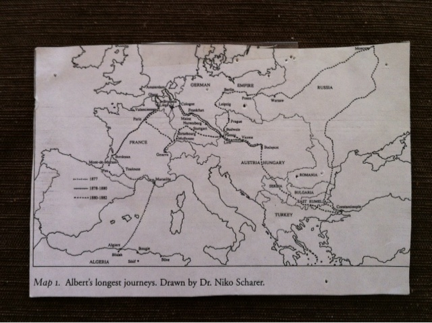

And then I began to walk. I found myself, discovered myself, walking onto planes to travel to various international artists’ residencies. Along with the photographs of Albert Dadas, I carried this map, which details Dadas’ longest walks:

I found myself in Mojacar, Spain and Lasswade, Scotland. I discovered myself in Chevigny, Switzerland and Ménerbes, France, places Albert might have walked. I walked and walked, and was often really, really lost (literally, but all the other ways too). Not knowing how I got there, the song of him in my head.

One time, I found myself walking in the misty Pajottenland in Belgium, waiting for this man who discovered himself in this place and that one, whole countries away from home, not knowing how he got there, to walk out of the mist. This man who covered a lot of ground and yet had such trouble navigating the world. Who among us hasn’t? That’s another part of the research I inadvertently did for this novel — remembering those times I was really, really lost, existing outside of time and space, unsure I would ever return. There I was, an American in a mesmerizing Flemish landscape dreaming about a Frenchman dead for over a century, a man who trashed his life in order to walk and walk and walk. In search of what? What was I in search of? I thought of the Wislawa Szymborska poem, “Could Have.” “So you’re still here? Still dizzy from another dodge, close shave, /reprieve?/One hole in the net and you slipped through?” It’s a fucking miracle, this life. That moment in the mist, that fleeting intensity of feeling, that went into the book too.

+++